Hello folks! While I am still basking in the thrill of having released The Strife of Camlann, I am trying to get back into talking about various aspects of the world of King Arthur. Today we’re going to meet the semi-legendary Pictish warlord, Caw, a character who first shows up in chapter five of The Retreat to Avalon, but features in all the books of The Arthurian Age series. He’s that interesting.

Caw is often referred to as Caw O Prydyn, or Caw of Pictland. Prydyn, an early Welsh name for Pictland, often becomes confused with Prydein, which becomes Prydain, which is the modern Welsh term for the Isle of Britain. However, medieval Welsh literature, including Culwhch and Olwen, all refer to Caw as ruling in “Pictland”.

Most people, when they think of Pictland and the Picts, think of the tribes living in Scotland north of Glasgow and Edinburgh. That is correct for the later medieval period, but as I detail in this article, there were “southern Picts”, who lived as neighbors to Britons in southern Scotland, at least up to the early medieval period, when they were probably absorbed into the local Gaelic and Brittonic cultures. In fact, in The Life of Gildas, Caw is said to live in ‘Arecluta’, which is Alt Clut in my series, a kingdom ruled from modern day Dumbarton, near Glasgow, Scotland.

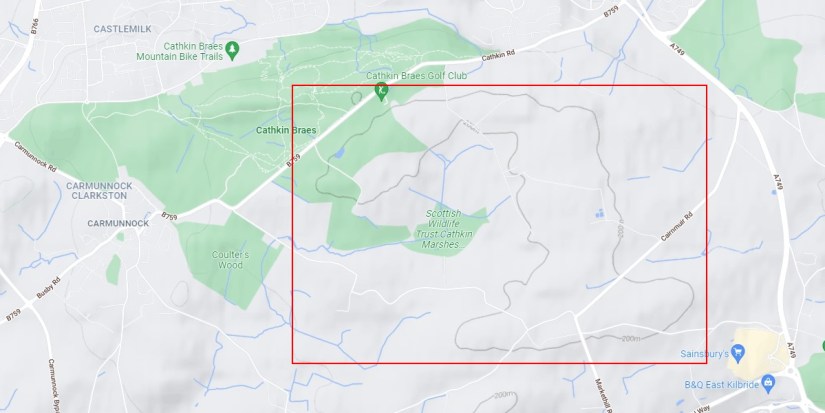

Moreover, there are clues to a more specific region: the Cathkin Hills, which lie to the southeast of Glasgow. The 11th century Life of St. Cadog, describes Caw as living near Mount Bannauc in the Cathkins. Bannauc (from Brittonic *Bannacon) means “a horn-like place”. Much like my eureka moment in finding a home for Gawain in Pollog, I was thrilled to find that the tallest hill in the Cathkins is actually a ridge shaped much like a horn!

This hill is also less than five miles from the location I use as Gawain’s family home at Pollog, which made it natural for our hero, Gawain, and the family of Caw, to have some interaction. If you’ve read The Retreat to Avalon and The Strife of Camlann, you’ll understand how big a deal this is.

So having established a location for Caw, what else do we know about him? Well, aside from being a Pict, he is called a King of Arecluta. There is evidence that Picts lived with Britons in the region, but Alt Clut was firmly controlled by Britons well into the ninth century, and never controlled by Picts. In this post-Roman and pre-feudal era, the boundaries between “kings”, “chieftains”, and “warlords” was a hazy subject. Based on what we know, I describe Caw as a warlord under the king of Alt Clut.

Caw was described as a craftsman, which is a hint to his existence having an ancient provenance. Craftsmen were one of the few people who had virtually unfettered access to dark age society. Class seems to have been less tied to lineage in this era, so anyone capable of amassing enough wealth (land), including a skilled craftsman, was capable of becoming a warlord. In fact, the Welsh term “gwledig” (literally ‘landholder’) is a frequent title for a warlord.

The other major mention of Caw is in the Welsh poem, Culhwch and Olwen. Written in the 11th century, it seems to have much older roots, describing archaic customs and values. The poem includes a long list of people attending King Arthur’s court, including 19 sons and 1 daughter described as Caw’s children. Caw plays a major role in the poem, in which a monstrous, magical boar is hunted as part of the bride-price for Arthur’s kinsman to win his bride. In fact, Caw is described as having dealt a major blow to the boar and taken it’s tusks, as well as other important tasks within the quest.

The characters in The Arthurian Age seem to write themselves, and they never fail to surprise me with the way their places in history and legend seem to come together like Lego blocks. Caw’s introduction in The Retreat to Avalon was fun, and I look forward to seeing him again. But as big a deal as Caw is, his children are particularly notable.

Also appearing in chapter 5 is Caw’s daughter, Cwyllog. She plays an interesting role in book 1, but a very important role in book 2. Without giving away any spoilers, I will just say that I did not invent the story of who she married, and the rest of her story seemed to just fall right into place.

Hueil, Caw’s eldest son, makes a brief appearance in book 1, but we will see him again. The most fascinating of Caw’s children, however, is the one person from Arthur’s era whose writings have survived to this day. Gildas! Not only do his writings survive, but they give us many fascinating clues to events and people of the Arthurian Age.

Thanks for stopping by and feel free to comment! If you’re intrigued by this exciting era and haven’t read The Retreat to Avalon and The Strife of Camlann, please pick up a copy. And I’d be so grateful if you left a review on Amazon or Goodreads! It really is the best help an author could ask for.

Something like this in Irish.

Tá an scian san fheoil. Ní fhéadfaidh aon duine dul isteach ach laochra, fir ceardaíochta agus filí

Caw being a craftsman and having a degree of independence is interesting. There are legends from other areas of a smith in particular being subject to servitude, Daedalus, Weyland and the Saxon Thegn when he moved to, say to newly conquered lands in Devon, being allowed to take his smith with him. But, the proclamation,that I may have got a bit wrong, from The Tain and other Irish sources about attendances at feasts “the knife is in the meat, let no man enter lest he be a warrior, a man of craft or a poet”

Hi Edwin, it’s no surprise that the Irish and the Britons, both Celtic cultures, shared this particular custom. In Culhwch and Olwen, when Culhwch arrives at Arthur’s gate, the porter won’t let him in, saying, “The knife is in the meat, and the drink is in the horn, and there is revelry in Arthur’s hall, and none may enter therein but the son of a king of a privileged country, or a craftsman bringing his craft.”